Legos, placemats, and community mapping

"I have always felt that the action most worth watching is not at the center of things, but where edges meet. I like shorelines, weather fronts, international borders. There are interesting frictions and incongruities in these places, and often, if you stand at the point of tangency, you can see both sides better than if you were in the middle of either one." —Anne Fadiman

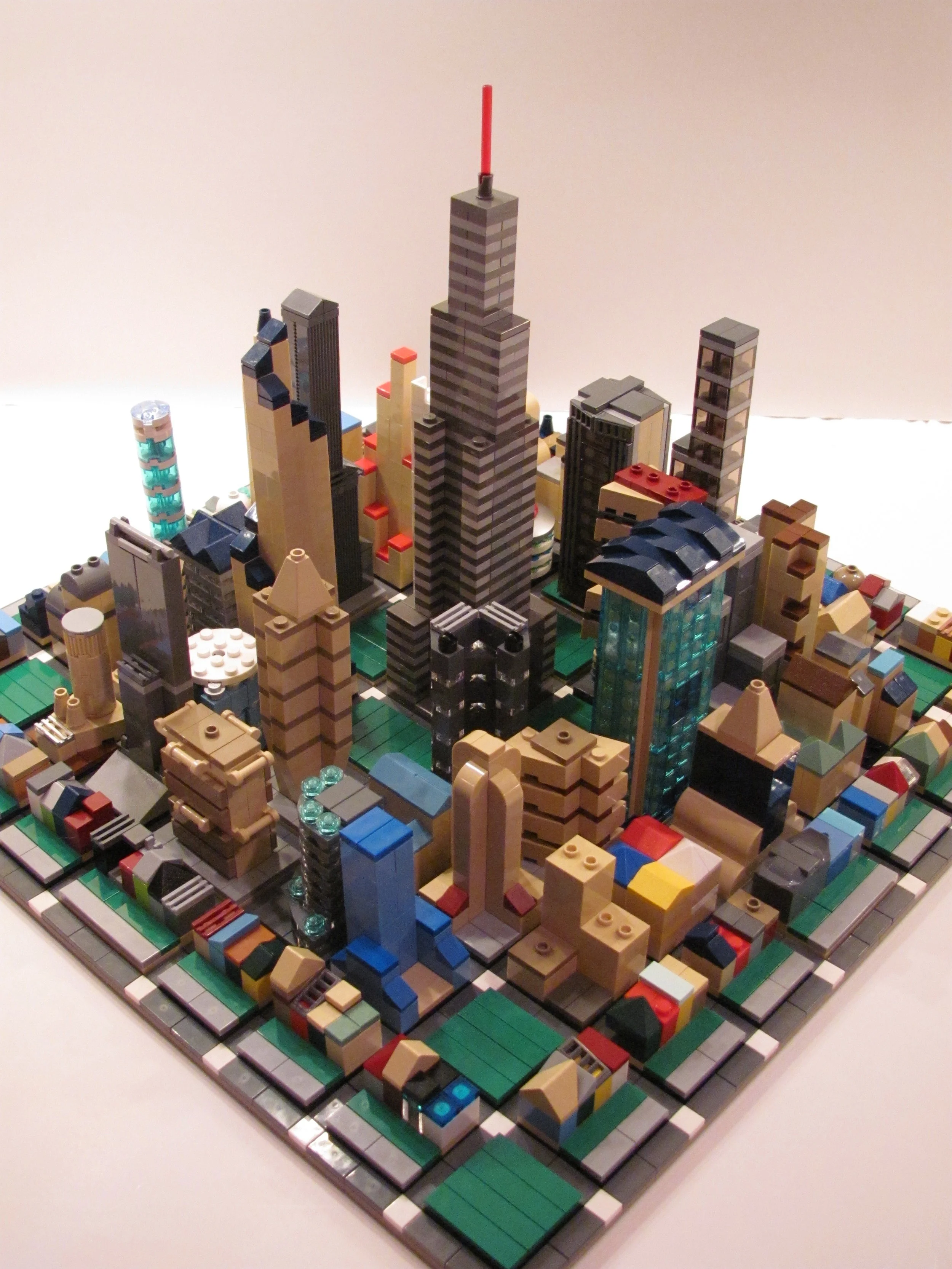

At the age of seven, with 64 Crayola Crayons in precise rainbow order at my disposal, I became the world's youngest cartographer. I would make maps of the eclectic Lego cities I built, so the Lego Jedi, Stormtroopers, firemen, and cowboys knew how many city blocks (no pun intended) they needed to travel to get across the land. And every evening, when I would I retire from my adventures and have dinner, I ate (and colored) on a placemat map of the United States that let me learn more about the various communities that make this country so diverse. Maps helped me better understand the places I had been to and they inspired me to dream about the places I could go.

My fascination with maps heightened when I transitioned into middle school and learned that in addition to their navigational purposes, maps showed the relationships between places and people by displaying information about population and geographic features. I was intrigued by the different kinds of maps and how some represented physical characteristics while others displayed human ones.

As I got older and my perspective on the world widened, so, too, did my understanding of maps. I learned that maps weren't just used to help people get places or to show how people were together; maps often illustrated how people were divided and how communities were fractured. Maps of select electoral districts in North Carolina show how boundaries are gerrymandered for a political advantage. Food desert maps in Boston highlight the neighborhoods that lack grocery stores, farmers markets, and other healthful food options. In St. Louis, census maps show the city's dividing lines: Delmar Boulevard serves as the Delmar Divide, where the area north of Delmar is more than 90 percent black and has less resources than the area south of Delmar that caters to a more privileged and predominantly white population. These aforementioned maps show the divisive areas of these communities and present a stark contrast to the maps of my open Lego communities where the Lego Jedi shared houses with the Lego Stormtroopers and the Lego firemen rubbed elbows with the Lego cowboys. Furthermore, the resources in my Lego communities were spread amongst the various populations in an equitable manner. When I constructed those cities, every single block I placed was done so with a purpose.

I now realize that my fascination with maps is fueled by my desire to understand and build better communities through civic engagement. When I look at maps and the visual stories they tell, I imagine the interventions that people and community organizations must make to turn vicious social, economic, and political cycles into virtuous ones. And although there are countless organizations and individuals addressing the social issues I mentioned (and so many more), it takes time and deliberate efforts from stakeholders across spectrums for diverse populations and organizations to get what they need to thrive (e.g.—the Jedi in our communities need to work with the Stormtroopers).

The apartment I live in today is lined with maps. I have a gigantic map of the United States. I have maps of places I've been to and places I want to go. And covering my wrist and resting on the back of my hand is a map watch of the world. When I look at the back of my hand and the relationship that countries around the world have with each other, I realize world that unlike my Legoland, this world isn't made of plastic. Mapping out better communities takes being conscious of everyone's needs and it begins with recognizing the complex and compelling stories that maps tell us every single day.

![Issue 2: "Place" [a letter from the editor]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/57544a60f8baf31c273a237d/1482548027446-4EPRVQS8AZV6CDAZ8TVR/omakase_issue2_cover.jpg)